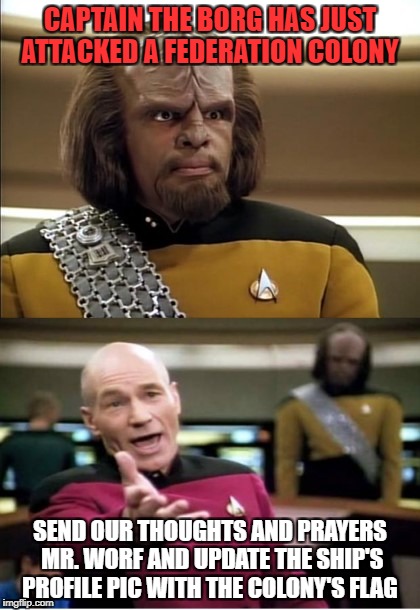

Slacktivism is the act of engaging in visible displays of support for a cause at little to no cost, while lacking any genuine intent to contribute to tangible change (Kristofferson, White, & Peloza, 2013). Although social media empowers individuals to launch grassroots campaigns, organize charitable efforts, and rapidly generate support for various causes, it also facilitates superficial participation with minimal real-world impact. Common examples include wearing bracelets or pins, signing online petitions, using hashtags, and the ubiquitous Facebook like (Kristofferson et al., 2013).

Importance

Slacktivism, hashtag activism, or this author’s preferred term “pseudo participation” is an important area of research due to the vast amount of resources involved in modern social activism. Political campaigns, disaster relief, charitable donations, and other causes are all shaped by the rise of social media. Because social platforms are easily accessible and – unlike traditional mass media – enable two-way communication, they have the potential to reduce the influence gap between large institutions and individual users. For example, social media allows almost anyone to participate directly in political campaigns or join action groups, increasing their sense of agency and investment in society (Kwak et al., 2018).

However, that same ease of access can create a false sense of meaningful participation – one unconnected to risk, effort, or real-world effect (Foster et al., 2019). More concerning, as social media begins to mirror traditional media in its trickle-down communication structure (Chou et al., 2020), it is increasingly used by established institutions as well. In such cases, token acts of support may reinforce self-delusion and, paradoxically, leave individuals more disengaged than if they had not participated at all.

Main Takeaways: Analyzing Pseudo Participation

Social media, though now ubiquitous, is still a relatively new element of society. The debate between active and passive participation, however, is not. In 1970, faced with the rise of television culture, Gil Scott-Heron famously declared, “The Revolution will not be televised,” expressing his belief that only real-world action could drive meaningful change (Glenn, 2015). Nearly half a century later, Andrew Sullivan responded to the 2009 Iran uprising by proclaiming, “The Revolution will be Twittered,” highlighting the growing role of digital platforms in social movements (Glenn, 2015).

The truth lies somewhere in between. While tweets and Facebook posts can easily be dismissed as white noise, a protest of 50,000 people – organized through those very channels – is much harder to ignore. Social media blurs the line between passive expression and real mobilization.

This dynamic applies to non-political causes as well. When Hurricane Harvey struck near Houston in 2017, causing over $125 billion in damages and displacing thousands (New York Times, 2017), social media played a key role in mobilizing relief. Platforms like Facebook helped organizations such as Samaritan’s Purse recruit over 10,000 volunteers (this author included) to assist in cleanup and recovery efforts (Samaritan’s Purse, 2017). Although no data exists on passive responses such as likes or hashtags – as Twitter and Facebook do not release participation statistics – the anecdotal evidence suggests that social media remains a net positive for activism.

Research indicates that the visibility of one’s actions predicts the likelihood of deeper involvement. Observable token efforts – like hashtags or profile filters – satisfy the need for social recognition and may reduce the drive to do more. In contrast, less visible forms of participation often activate a person’s sense of internal value, increasing the chance of further involvement (Kristofferson et al., 2013).

Charitable giving via social media also reflects this tension. E-pledges, while symbolic, carry no obligation if donors fail to follow through. Some people also distrust the validity of these pledges (Chou et al., 2020). Still, because the cost of solicitation is so low, even low conversion rates can make e-pledging an attractive fundraising tool.

Not all scholars agree that passive participation is inherently shallow. Some suggest it plays a meaningful role in what they call “information activism” – the collective awareness-building that amplifies causes over time. While passive participants may reject riskier offline activism as unnecessary or ineffective (Kwak et al., 2018), their digital actions may still have real-world consequences. Since collective action is often defined by intent, even minimal contributions that support a cause can be considered active participation (Foster et al., 2019). In theory, spreading awareness alone can create tangible social change – meaning token efforts may, over time, become part of a larger, effective movement.

Strengths and Limitations of the Research

A major concern in studying slacktivism through social media is the limited availability of usable data. Most major platforms treat engagement metrics and participation details as proprietary trade secrets. As a result, researchers must construct empirical models that attempt to simulate real-world behavior – a task complicated by the sheer scale and variability of online interactions.

One attempt to assess downstream participation following a token effort was conducted by Chou et al. (2020). In this study, 93 students were recruited under the guise of participating in a game to minimize behavior shaped by expectations. Each participant was randomly assigned one of three methods to “sign” a petition:

- Clicking a “like” button

- Signing with initials

- Signing with a full name

Participants were then asked to offer suggestions for improving the study. While all completed the initial task, only 47% voluntarily submitted suggestions. This controlled environment effectively measured the effort-to-outcome ratio but did not account for social observability or the differing motivations tied to visible versus private participation – key variables in real-world slacktivism.

In contrast, Kristofferson et al. (2013) conducted a real-world field study at the University of British Columbia. Leading up to Remembrance Day, researchers positioned themselves in a hallway near a student cafeteria and approached participants with one of three options:

- Public token: A poppy pin for veterans, placed visibly on the student’s clothing

- Private token: The same pin, provided in a sealed envelope

- No token: No pin offered

At the end of the hallway, participants were then asked to make anonymous donations. The results showed that students who received the private token donated an average of $0.85, while those with a public token gave only $0.35. This finding supports the idea that personal, internal motivation can be stronger than visible, performative gestures. Still, the uncontrolled environment of a university hallway means the findings should be interpreted with caution.

One common limitation across these studies is the use of student participants. While researchers took steps to ensure racial and gender diversity, the convenience sample heavily favored individuals between the ages of 20 and 30. This narrow demographic introduces bias and may not reflect the broader population’s behavior, especially across different age groups or cultural contexts.

Directions for Future Research

Existing studies tend to focus on isolated aspects of slacktivism, such as effort versus reward, or visible recognition versus personal value. While these are important building blocks, future research should aim to integrate these findings into more comprehensive behavioral models. This would provide a fuller understanding of how digital and physical activism interact over time.

One of the greatest challenges remains the limited access to social media data. This barrier could be addressed through the creation of experimental activist communities or by collaborating with existing groups willing to share participation metrics. With access to real engagement data, researchers could more effectively compare digital slacktivism with real-world follow-through.

Demographic diversity is another area needing improvement. Most existing studies rely heavily on university students – a group that represents only a narrow age and cultural band. Older individuals, as well as much younger users, may engage with social and political causes in distinctly different ways. Capturing those differences is critical for any model that aims to reflect the true spectrum of participatory behavior.

Conclusion

Casual observation may suggest that slacktivism is undermining traditional activism, but research reveals a far more complex relationship. Like most human behaviors, participation exists on a spectrum – and social media simply provides a new venue for both active and passive engagement. It did not create activism or slacktivism, nor does it define them.

More research is needed to fully understand whether digital participation displaces meaningful action or enhances it. What is clear, however, is that social media has permanently altered how causes gain visibility, and how people choose to engage with them – for better or worse.

References

Chou, E. Y., Hsu, D. Y., & Hernon, E. (2020). From slacktivism to activism: Improving the commitment power of e-pledges for prosocial causes. Plos One, 15(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231314

Glenn, C. L. (2015). Activism or “Slacktivism?”: Digital Media and Organizing for Social Change. Communication Teacher, 29(2), 81–85. doi: 10.1080/17404622.2014.1003310

Kristofferson, K., White, K., & Peloza, J. (2013). The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(6), 1149–1166. doi: 10.1086/674137

Kwak, N., Lane, D. S., Weeks, B. E., Kim, D. H., Lee, S. S., & Bachleda, S. (2018). Perceptions of Social Media for Politics: Testing the Slacktivism Hypothesis. Human Communication Research, 44(2), 197–221. doi: 10.1093/hcr/hqx008

Foster, M. D., Hennessey, E., Blankenship, B. T., & Stewart, A. (2019). Can “slacktivism”

work? Perceived power differences moderate the relationship between social media

activism and collective action intentions through positive affect. Cyberpsychology:

Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(4), article 6.

https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-4-6

Samaritan’s Purse. (2017). Help Hurricane Harvey Victims in Texas. Retrieved May 24, 2020, from https://www.samaritanspurse.org/disaster/hurricane-harvey/

The New York Times. (2017, August 26). Harvey, Now a Tropical Storm, Carves a Path of Destruction Through Texas. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/26/us/hurricane-harvey-texas.html